The Walkability app, developed by Active Cities partner Walk21, allows citizens of all ages and abilities to share their walking experiences. Sharing walking experiences helps communities and responsible authorities to understand walkable places and identify areas that need further improvement to make walking better for everyone. Walking should be safe and enjoyable for everyone. When it isn’t, we walk less, and loose the health, social, environmental, and economic benefits associated with living in more walkable places.

Written by Valentina Kroker (KU Leuven) and Carlos Cañas (Walk21)

In this article, we learn more about the importance and benefits of monitoring and measuring walkability, and how the app is influencing the number of walkers in the Dutch cities of Leeuwarden and Groningen.

Walkability can be considered as the extent that the environment supports and encourages people to walk within a reasonable amount of time and effort. It is difficult to put a single value on that ‘extent’ when we all have different needs impacted by our age, ability, gender and many other variables. What one person might consider ‘reasonable’ in terms of time and effort could be, and often is, very different from the value others might give it.

By providing more citizens with the opportunity to easily share their perceptions of the environments where they are walking, we can start to understand the reality of where people feel walking is safe, comfortable and enjoyable. Conversely, we can also start to visualise where it is perceived to be dangerous, difficult and unpleasant and learn who is being affected most, as well as what actions could be taken to make the walking experience better.

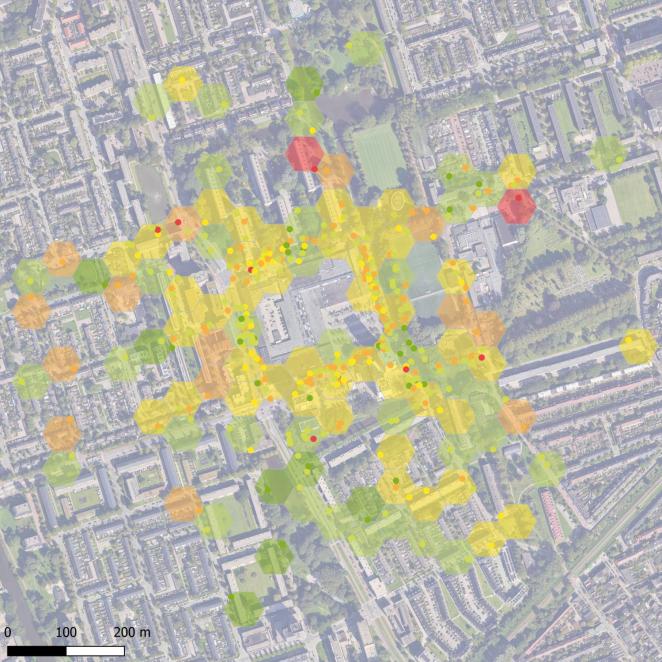

Groningen

This map displays the walkability surrounding the Groningen pilot site, using data collected through the Walkability App

The City of Groningen noticed that there are networks for every mode of transportation, including a network for cars, cycling, and public transport, but none for walking. Through the Active Cities project, the city is aiming to fill this gap by creating a ‘desired ’pedestrian network for the city at a neighbourhood level. The desired network has in turn inspired a Walkability Strategy to develop projects that support better walking experiences. The data collected with the Walkability App informed local policymakers about the experiences reported by people, specifically around the Paddepoel area and delivered an important baseline understanding of the network.

The temporary transformation from traffic space into living space of two areas close to the shopping mall is part of the Pedestrian Friendly Paddepoel pilot activities. Parking space will be removed and / or part of the street will be blocked from car traffic. The redesign adds walking and cycling space, green areas, and equipment to support active mobility and interaction.

Additionally, through the collection of walkability data, the city of Groningen can assess whether these temporary interventions and transformations enhance the walking experience, to what extent, and for who. Complementing the perception data collection, it was also important to collect objective data about pedestrian movement. During data collection, interviewers would spend 45 minutes interviewing people walking about their perceptions using the Walkability App before taking 15 minutes to count the pedestrians they see on the street.

Leeuwarden

In the City of Leeuwarden, permanent interventions are planned with the objective of placing pedestrians at the top of the mobility pyramid. The research site is part of a redevelopment site called Spoordok, a previous industrial estate now being developed as a mixed-use area with 2,000 dwellings. Colourful markings on the street are being added to symbolise the shift in priorities and help communicate upon entry, that the pedestrians are now the main users of the street while the cars are guests. The street connects temporary housing for Ukrainian refugees and other citizens in need of immediate housing.

By assessing the walkability experiences before and after the intervention, the city hopes to obtain data-driven evidence of the impact on the experiences of people living in the temporary housing. Furthermore, the results will help in the decision-making process of what is needed to reach the goals of the municipalities mobility strategy. A strategy based on the principle to increase space for walking (and cycling) and thereby achieve liveable streets and a healthy city environment.

The role of the Walkability App

Fundamental to this research has been the Walk 21 Walkability App. The app has been designed by a team of walkability experts, coordinated by the Walk21 charitable foundation. It enables citizens to share their walking experiences, and provide valuable insights into what makes places walkable and the improvements needed to make walking better for everyone.

The app can be downloaded by citizens and used as a direct reporting tool. More commonly, city teams are trained by Walk21 to use it as a recording tool for on-site interviews. It typically takes 2-3 minutes for people to share their experiences and over the course of a day teams can typically reach more than 100 people. Cities are mostly approaching Walk21 when they already have a project investment planned and want both a baseline assessment of current perceptions as well as a way to value the impact of change post intervention. The open-access data approach and charitable objectives of the NGO keeps the system affordable, the data accessible and the insights valuable.

All results have been made available through a report created by Walk21. First, information about the pedestrian was recorded, including their gender, age, and difficulty interacting with the environment. This allows us to create maps of the city from different perspectives to our own.

The reports also distinguishes between the overall summary of the pedestrian experiences (aggregated from records across the city) and experiences reported in each street. Therefore, we can compare the experiences on different streets and at different times with one another and see why some streets are more walkable than others.

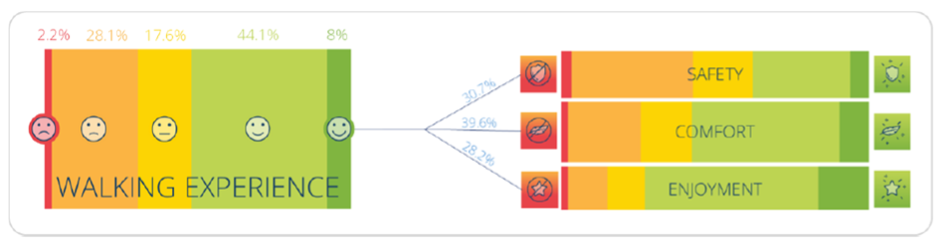

In the figure below, a breakdown of the data in the City of Groningen can be found. It shows the number of times each evaluation of walkability (very negative to very positive) has been mentioned and whether these experiences were based on safety, comfort, or enjoyment.

Interestingly, about 30 percent are either very negative or negative (red and dark orange) and about 52 percent were (very) positive (light green and green). About a third of the pedestrians mentioned safety as the main concern for their walking experience. Explanations of the factors that influenced these scores were outlined further in the reports.

Both projects in the Netherlands enjoyed the unique position of using the new and improved version of the Walkability app created by Walk21. Initially, there was a slight learning curve to learn how to best use it. However, concerns were mitigated through a training session led by Walk21 and KU Leuven. The session explained in detail how to use the app and ensure during the data collection phase everything is on track and the information gathered is useful.

Additionally, the teams behind the data collection learned that people are generally happy to contribute to the research and offer information about their walking experiences.

What happens next?

In partnership with several Active City partners, Walk21 has translated the app into 11 languages. (English, Portuguese, French, German, Italian, Swedish, Finnish, Dutch, Spanish, Czech and Greek). This reflects the demand coming from cities around the world to engage citizens and understand the reality of how walkable their current everyday trips are. For some, the motivations are increasing physical activity levels, others want to reduce emissions, congestion and reduce short trips by private vehicles. Either way, the evidence-based approach is proving helpful to projects in places as varied as Australia to Zambia.

The next steps for both cities are quite similar as the implementations are currently planned and created. The aim is to implement a second round of data collection after the interventions in the spring of 2025 to understand the overall impact. Over time, the City of Leeuwarden is also interested in comparing the impact of different walkability measures to obtain a more detailed understanding of what is most useful in different streets and public spaces to support the delivery of the wider mobility policy vision.

Active Cities knowledge partner KU Leuven will continue supporting the development of the projects and assessment plans and analysing the changes to walkability in both cities. PhD candidate Valentina Kroker plans to publish the results in an academic journal for her dissertation.

The Walk21 Walkability app is available to download for free from the Apple and Google stores