Flooding doesn’t always start with a broken dike. In Sweden, the municipality of Torsby and Karlstad University are studying what happens when a hydroelectic dam needs to release large volumes of water. This kind of controlled release may sound safer than a sudden breach, but for people living downstream, the effects can still be severe. The release is controlled, but the effect is not always clear beforehand.

As part of the FIER project, Karlstad University and the municipality of Torsby are working together to improve emergency planning and communication. Their goal: ensure that local residents know what to expect – and what to do – when large-scale water releases are necessary.

What makes it a controlled release if people are in danger and it could happen very fast that people need to know more about the risks?

Mapping the valley and its risks

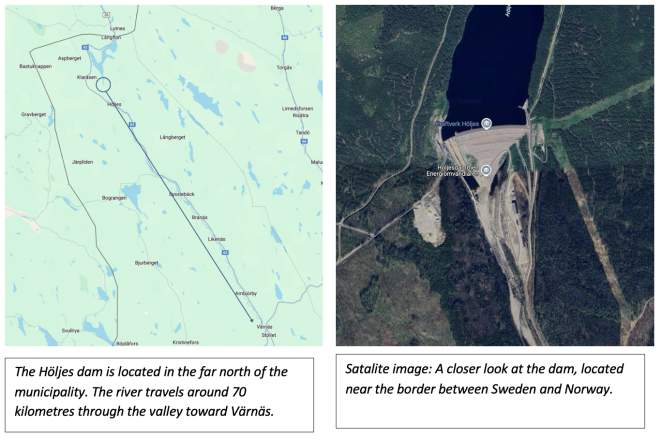

The municipality of Torsby stretches along the Klarälven river, from Höljes in the north to Värnäs in the south. This 70-kilometre stretch is dotted with small towns, forests, and farmland. The river flows past the Höljes dam, which is designed to manage water levels by releasing water when necessary – usually every 20 to 30 years.

The map below shows the location of the dam (indicated with a blue circle) and the direction of the water flow (arrow). The second image shows satellite photos of the dam area.

A history that informs the future

In the mid-1990s, the Torsby region was hit by severe floods caused by dam releases, affecting large parts of the valley between Höljes and Värnäs. Two long-serving members of the local fire department – both of whom were active during the floods – now share their experience to inform future emergency planning.

Today, dam releases occur approximately once every 20 to 30 years. The aim of the FIER pilots in Karlstad and Torsby is not to cause alarm, but to raise awareness: how do you prepare when the landscape can change in hours? And how do you reach the people who need this information most?

The book bus meets residents along the Klarälven river between Höljes and Värnäs.

From the valley to the village

The Torsby pilot focuses on improving local knowledge of flood risk. In many parts of the region, people are well aware of the risks during springtime, when snowmelt raises water levels. But in summer, when tourists arrive and locals are less alert, awareness tends to fade.

To get a clear picture of current public knowledge – a so-called "zero measurement" – the municipality conducted interviews, distributed questionnaires and even travelled through the valley with a book bus to talk with residents in person.

They asked questions like: How much water can the dam safely release? Which houses, sectors or roads could be affected? How do people receive warnings? In cooperation with local media, they also included a QR code in the newspaper to invite people to participate in the survey.

Simulations, scenarios and communication

Karlstad University took a similar approach, with a focus on inclusive communication and emergency planning. A recent workshop brought together residents, emergency services, and people with lived experience of past floods to explore what kind of help different groups might need. For example: What happens if a main road becomes inaccessible? How can we support older adults or people with disabilities in those situations?

Rather than working from worst-case scenarios, the region maps what is likely to happen if the dam releases water under different conditions. This means looking at the amount of water, the direction and speed of the flow, and how this affects local infrastructure. These insights will feed into regional risk maps – and help strengthen early warning systems.

A broader context

Recent weather events underline the importance of preparedness. In Sweden, the Gothia Cup football tournament was temporarily paused due to extreme weather – a reminder that even short-term storms can have serious consequences (SVT). Meanwhile, a study in Texas showed how a lack of flood risk awareness worsened the impact on local communities (CNN).

These examples, though different in nature, show that local knowledge and timely communication can make a real difference – both in everyday life and in emergencies.

By combining data with dialogue, and planning with personal stories, Karlstad and Torsby are building more than maps. They’re building trust.

Working together, thinking ahead. That’s the FIER way.