In its first 2026 webinar, GLEAM NSR explored a central question for European cities: How, when, and for whom do zero-emission zones (ZEZs) work? Drawing on the Netherlands’ 10-year journey and Rotterdam’s city-level experience, the discussion highlighted that implementation is not just technical, but deeply political, institutional, and practical.

A 10-Year Journey: From Experiment to Implementation

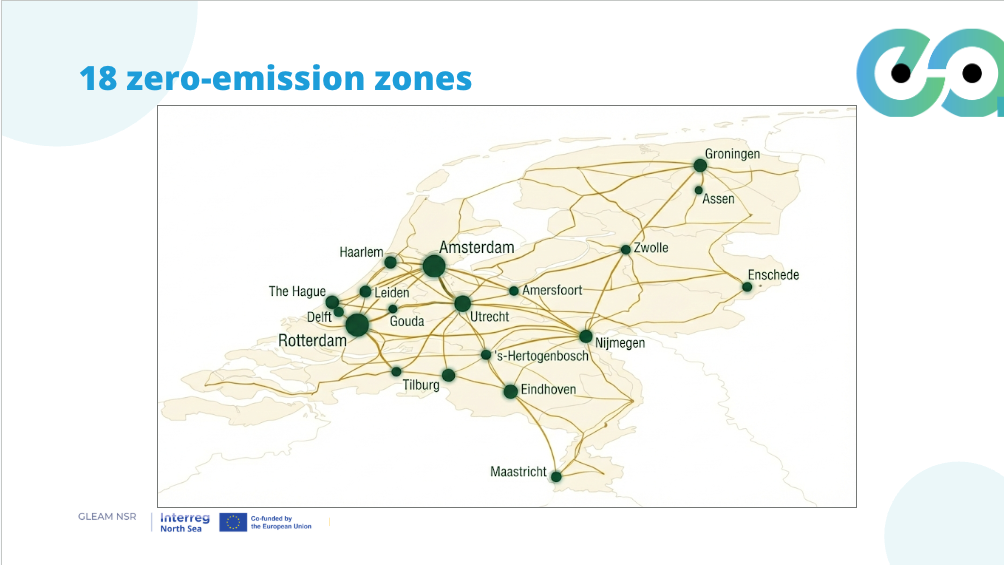

Map of zero emission zones

Researchers Paul Buijs and Anna Dreischerf from the University of Groningen described the Dutch pathway in three phases:

Early local experimentation in front-runner cities such as Rotterdam, Groningen and Amsterdam

National preparation and formalisation, including alignment with the Dutch Climate Agreement and EU climate targets

Local implementation and harmonisation, with enforcement, exemption systems and communication structures put in place

Today, 18 Dutch cities operate zero-emission zones, with a national ambition of 30-40 zones contributing to a 1 megaton CO₂ reduction by 2030.

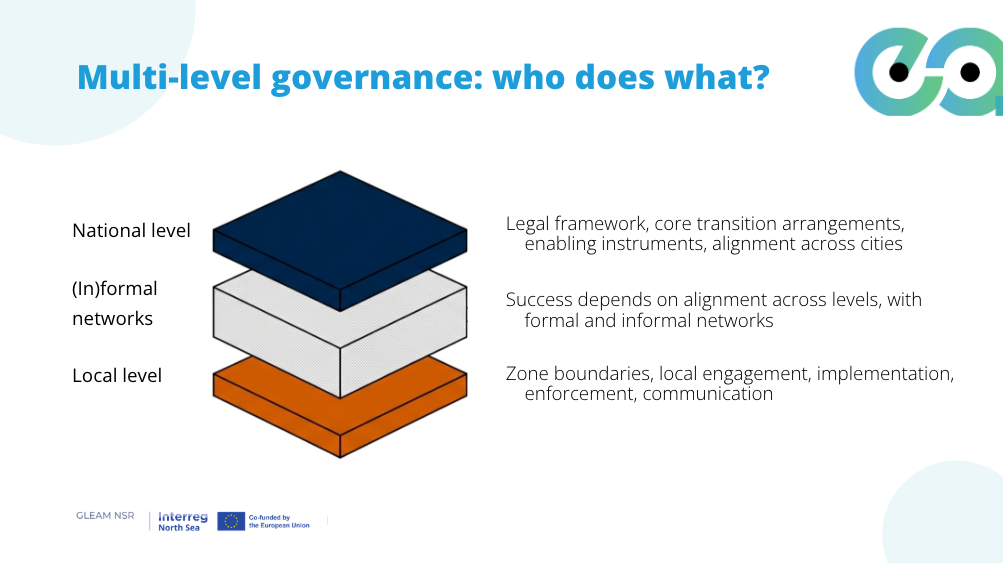

A central lesson is that success depends on multi-level governance. Municipalities define zone boundaries and manage local engagement. The national level provides the legal framework and transition rules. Crucially, informal and formal networks between city level elected officials and policymakers, with the support of industry lobby organizations, helped maintain alignment - especially during moments of political uncertainty where the zero-emission zone were almost entirely cut.

Explanation of 10 year process to ZEZs in the Netherlands

Visual representation of the levels of governance in the Netherlands in relation to ZEZs

Bottlenecks and Trade-Offs

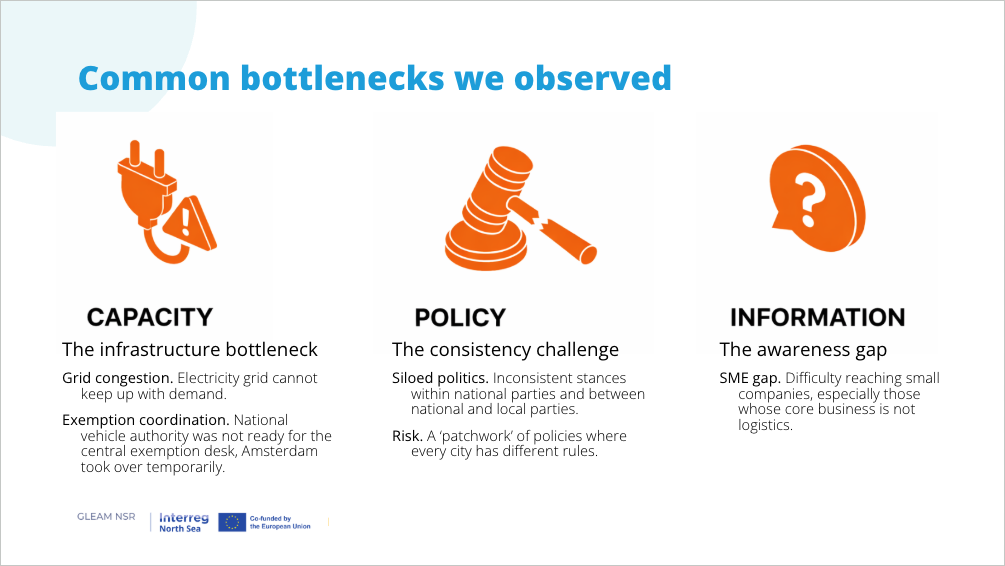

The Dutch experience also reveals structural challenges:

- Grid congestion: The electricity network cannot always keep pace with electrification demand.

- Exemption coordination: Setting up a harmonised national exemption desk, though important, proved too complex to implement.

- Policy consistency risks: Without harmonisation, cities risk creating a “patchwork” of differing local rules.

- The SME awareness gap: Many small companies, especially those whose core business is not logistics, are difficult to reach.

Given that 99% of EU road carriers have fewer than 50 employees, design choices around clarity, timelines, and exemptions are not minor details, they are decisive.

Explanation of bottlenecks for ZEZs

Rotterdam: Implementation in Practice

From Rotterdam’s perspective, implementation raises ongoing dilemmas.

- Choose your battles: Even seemingly straightforward ideas, such as proactively warning companies when exemptions expire, require contractual and administrative adjustments.

- Privacy matters: Efforts to better tailor flanking policy by linking vehicle data with economic sector information must comply with strict data minimisation principles.

- Space is political. Early expectations of large-scale hub demand proved overestimated. Meanwhile, pressure grows for indoor loading space, microhubs, and parking and charging for light electric freight vehicles.

- Efficiency remains unresolved: Should cities favor fewer large vehicles or more small ones? Without a structured view on preferred vehicle types by location or time of day, “downsizing” risks becoming an unexamined assumption.

Beyond Zero Emissions

Zero emission is not necessarily the end station. Even with fully electric fleets, cities must still address congestion, safety, accessibility, and resource use. Rotterdam also cautioned against conflating “autoluw” (low-car) policy with freight regulation: passenger cars account for the vast majority of urban traffic, meaning freight-focused measures alone have limited impact. Unlike subsidies or pilots, ZEZs are regulatory instruments. They restrict access while offering long transition timelines. That combination, restriction plus predictability, appears to drive market change. The Dutch case suggests that zero-emission zones work when they are clear, harmonised, SME-proof, and supported across governance levels. But their long-term success depends on continued alignment, and on cities being willing to ask what comes next.